Wetland Facts

Wetlands ['wĕt-lăndz]

Ecosystems that either have shallow water standing above the soil surface or have a soil saturated with water for periods of time.

What is a Wetland?

Scientists, ranchers, farmers, and others have all been debating the definition of a wetland for more than five decades. In fact, there are over 50 official definitions for wetlands!

The most accepted definition says that wetlands are ecosystems that either have shallow water standing above the soil surface or have soil saturated with water for periods of time. These areas also need to produce certain soils or plant life typical for a wetland area. A true wetland also includes areas that, even if they are not covered by surface water, sometimes have water-logged soil.

Your senses can help identify wetlands. Check the soil — is it damp to the touch? Does it sparkle with liquid? Can you literally squeeze water out of the soil? Do you see plants, such as sedges or cattails, that live in wet soil? Do you hear frogs or see salamanders?

But what if a pond has already dried up for the season? How might you identify it as a wetland? Observe the area carefully. Look for cracked, dried mud. Check for damp soil under the surface. Hunt for watermarks on the shrubs, trees, or rocks. Sometimes you may find grasses and twigs collected at the base of other plants. Leaves coated with a thin layer of sediment may also be lying on the ground. If an area displays these signs it is probably a wetland.

The Importance of Wetlands

Wetlands can be found all over the United States — and also the world. They are literally “wet lands,” at least for part of each year. Wetlands can be fresh water, salt water, or a mix — called brackish. Most of the wetlands in the Rocky Mountain region are freshwater, and many of them dry up each year. Whether permanent or seasonal, wetlands provide valuable habitats for insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and some fish and mammals. Because of their abundant animal life, wetlands also attract scientists, hunters, birders, artists, and other people who enjoy nature.

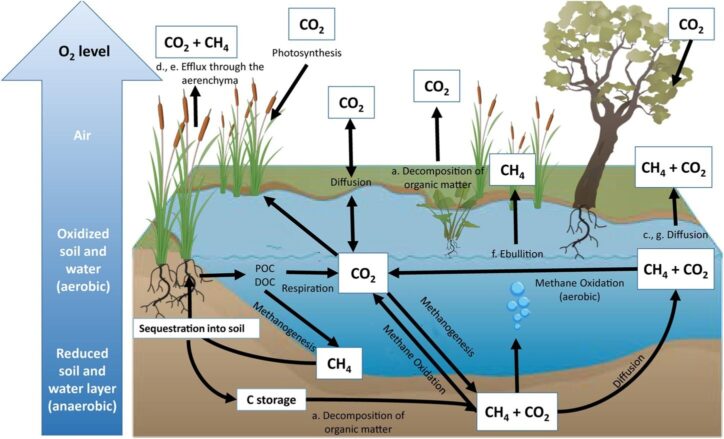

A wetland is important to our environment. Plants continually change carbon dioxide into oxygen to produce energy and food through photosynthesis. The foods created by the plants are spread by floods, storms, and tides. When plants die, they form the first level of food chains and webs. Bacteria and other microscopic life feed on the dead plants, and then the microscopic life is consumed by fish, worms, birds, and insects.

The dense vegetation of wetlands creates a natural water treatment system that is better than anything that humans have ever created. Water slows as it flows downstream because of the heavy plant life in a wetland. The slowing water causes sediments and pollutants to settle to the bottom. Some plants soak up the toxins that otherwise would wash into our lakes, rivers, and coastal waters. Bacteria in the water and soil can also remove wastes, including the body wastes of animals and humans. The water soaks into the ground to help fill aquifers and other groundwater resources. These resources supply a majority of the drinking water for many regions of the United States.

In addition to slowing and cleaning water, a wetland's dense vegetation can protect a nearby shoreline from waves that might threaten human habitations. Whether inland or near coasts, wetlands act like giant sponges, absorbing water during floods and storms.

Wetlands provide another important service for people. These habitats are also popular places for recreation. For example, bird watchers are the fastest-growing group of outdoor fans, and they can often be found around wetlands watching waterfowl, songbirds, raptors, and shorebirds. People who hunt, fish, canoe, and photograph wildlife also rely on wetlands and contribute lots of money to our economy each year.

Prior to the 1950s, many people in the United States considered wetlands to be dangerous, dark, damp horrible places full of snakes and alligators that could kill you or mosquitoes that would spread diseases. As an example, one big wetland in southern Virginia was named The Great Dismal Swamp (“dismal” means depressing and dreary). Fortunately, attitudes have changed, and today this same wetland is a National Wildlife Refuge loved by bird watchers and scientists as a shelter for wildlife and wild flora.

Because wetlands were once not considered important, many people around the world dredged, drained, and filled in as many wetlands as they could. These lands were turned into farms, pastures, towns, and cities. Today, when you walk many of the streets of major cities such as Chicago, Boston, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., you are walking upon filled-in wetlands. This is also true even in Boise, Idaho.

Native peoples of the Americas did not share this negative view of wetlands. Archeological evidence shows that the ancient Mayans built raised fields in the wetlands of Central America. The raised land would keep the root systems of their crops above the waterlogged soil while allowing access to the irrigation water. The native peoples around the Great Lakes region in the U.S. gather foods that grow in the wetlands, such as cranberries and wild rice, which can grow only in healthy and clean wetlands. Ancestors of the Nez Perce traveled to the Palouse region where they harvested camas bulbs that grow in seasonal wetlands of this fertile grassland. The Coeur d'Alene tribe harvests a wetland bulb known as a water potato and considers it so important that they celebrate it in a tribal holiday. Native peoples harvested other wetlands plants such as alder, lovage, and horsetail. They also hunted animals that lived in the wetlands, such as ducks and beaver.

Scientists around the world have been studying wetlands to understand not only how they function and benefit ecosystems, but also how they contribute to human health and economies. For example, timber companies harvest trees from the swamps and wet forests of the southeastern United States. In some wetlands, dense layers of dead plant material, called peat, can become compressed over time. This resource can then be mined to provide a soil conditioner for gardens and to provide fuel. Many regions in the southeastern U.S. depend on healthy wetlands for abundant harvests of fish and shellfish. For centuries, people have harvested wetland plants such as sedge, bogbean, and red mangrove and used them for medicines.

Wetland Soils

If you can squeeze a fist full of soil into a ball, you've got soil with no room for much oxygen. And that's bad news for most plants, because oxygen is an important part of their respiration. They absorb the oxygen from the soil through their roots. This type of soil is called anaerobic.

Oxygen-starved soils often smell like sulfur or rotten eggs due to the bacteria that thrive under these conditions. The dampness also causes chemical reactions in the elements of the soil. For example, iron will rust and cause the soil to appear orange.

Scientists recognize two major types of wetland soils: organic and mineral.

- Organic soil has a substantial amount of decomposing plants; this kind of soil is often black or dark brown.

- Mineral soil contains few decomposing plants; instead, it is made of materials such as clay, sand, or silt. Wetland mineral soils may be gray, greenish, or bluish-gray; they also might be mottled.

Soil content also determines the speed of draining. For example, water seeps through sandy soils faster than clay soils. Sand particles are large and irregularly shaped; they have more air pockets through which water can move. Clay particles are smaller and can compress when wet; their smaller air pockets fill more quickly and completely.

Wetland Plants

Plants that live in wet soil must adjust to the lack of oxygen. Reeds and sedges, found in freshwater wetlands, have hollow structures that allow the little oxygen they gain to travel quickly through the plant.

Mangrove trees, found in saltwater wetlands, have a tangle of roots that are exposed from time to time to the atmosphere as the tides ebb and flow. Cypress trees, which grow in freshwater swamps, have knobs or “knees” of root material that emerge from the water; scientists believe that these “knees” absorb oxygen. The roots of floating plants, such as duckweed or lilies, dangle into water and absorb oxygen. Wetlands plants also must be good at absorbing other nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus.

Wetland Wildlife

When you enter a wetlands habitat, you are entering an environment that supports thousands of plants, hundreds of birds, and almost all of the fish and shellfish that we consume.

Permanent residents of wetlands in the western United States include algae, bacteria, and other micro-organisms; animals such as the mosquito, dragonfly, and numerous aquatic insects, plus toads, the leopard frog, tiger salamander, pupfish, crayfish, beaver, muskrat; and plants such as sedges and bulrushes, berry bushes, shrub willows, and cottonwoods.

Seasonal residents include the American peregrine falcon, the whooping crane, ducks, geese, swans, numerous sparrows and warblers, bitterns, avocets, black-necked stilts, deer, elk, black bear, brown bear, bald eagle, osprey, trout, and salmon.

Almost half of the threatened and endangered species in the United States rely directly or indirectly on wetlands for their survival. In Idaho, for example, 49 species of rare plants and 29 species of rare animals depend on wetlands.

Wetlands also serve as nurseries, cafeterias, and homes for fish and other aquatic species that we humans love to eat. Studies estimate that wetlands provide habitat at some point for at least two-thirds of the fish caught and sold in the United States. We also collect foods that grow in wetlands, such as wild rice, blueberries, cranberries, mint, and onions.

A Wetland by Any Other Name

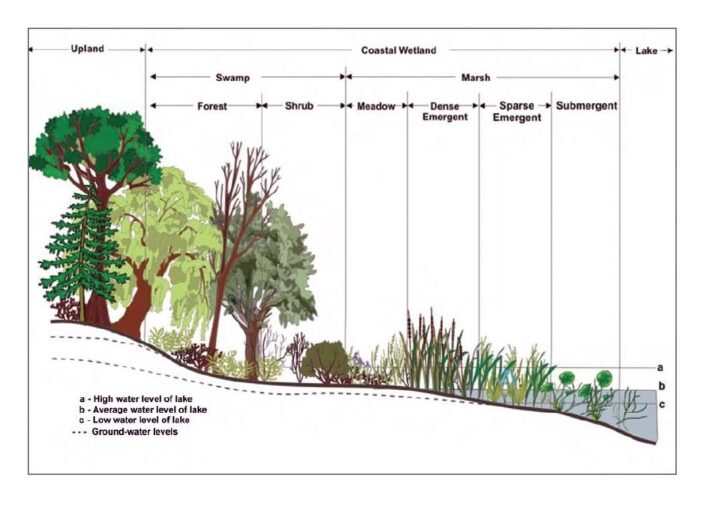

Wetlands are found all over the world and, depending upon the environment and local conditions, they take on specific names and properties. Wetlands are known by lots of different names: bog, bottomlands, fen, marsh, mire, moor, muskeg, peatland, playa lake, pocosin, prairie potholes, riparian, slough, swamp, or wet meadow.

Here are some of the common types of wetlands:

Marine Wetlands

These saltwater wetlands are located along coasts. Water levels rise and fall with the daily tides and can be subject to the force of waves, storms, and ocean currents. Characteristics of marine wetlands vary with the level of tidal, wave, and current effects. Salt-tolerant plants are dominant.

Estuarine Wetlands

Coastal wetlands where fresh and saltwater mix are known as estuaries. Estuarine wetlands usually have some access to oceans, with significant inflows of freshwater. The wetlands of estuaries, such as at the mouth of the Columbia River, also provide essential resting and feeding places for salmon. Young salmon spend at least a short time in these quiet waters before moving into the ocean. Fall chinook salmon spend months there before beginning their adult journeys. Returning salmon also may rest briefly in the nutrient-rich waters of the estuaries, consuming one last massive meal before they journey to their spawning grounds.

Riverine Wetlands

Wetlands found in the channels of rivers and streams are called riverine wetlands. Riverine wetlands occur along streams, rivers, and irrigation canals throughout the United States. They are particularly noticeable in western states such as Idaho because they form ribbons of trees and shrubs in otherwise arid landscapes. They typically support dense vegetation of trees such as cottonwood and quaking aspen, shrubs such as mountain maple and red alder, and grasses. These plants help bind the soil of banks, protect the banks from erosion during floods, and trap additional sediment from floodwaters.

Lacustrine Wetlands

These freshwater wetlands form around the perimeter of lakes and reservoirs. They are larger than 20 acres or contain water depths in excess of 6 feet. Like marine and estuarine wetlands, lacustrine wetlands are exposed to wave action.

Palustrine Wetlands

Isolated, inland wetlands not associated with lakes or reservoirs are called palustrine wetlands. Smaller and shallower than lacustrine wetlands, palustrine wetlands include wet meadows, bogs, potholes, and playas.

Wetland Loss

In a few hundred years of settlement, the United States has lost more than half of its original wetlands — from an estimated 220 million acres in the contiguous states to less than 110 million acres. Currently, the United States loses more than 70,000 acres of wetlands every year, and this pace probably won't slow.

For hundreds of years, agriculture has been the main destroyer of wetlands among our many activities. If a field was too wet in the spring, farmers would dig a ditch to drain off the water. When the country and the world demanded more grain, the federal government paid people to fill in wetlands. And when family farmers struggle to make their mortgage each month, it's hard to ask them not to plow every square inch of ground.

Urban expansion gobbles up more large chunks of wetlands. Vast acres of marshes in multiple areas of the U.S. were dredged or filled in the twentieth century to make way for freeways, airports, industrial sites, business buildings, and thousands of homes.

Most people barely notice the millions of small wetlands lost to bulldozers. These small wetlands, which often last only a few months each year, are vital purifiers of surface water, rechargers of groundwater, and providers of habitat for wildlife.

Many acres of riverine wetlands have been damaged by livestock grazing. Livestock not only consume the vegetation, but they also tend to remain in the same area for an extended period of time. Their movements to and from riverbanks can create gullies and otherwise undermine the banks.

Our construction efforts, whether building roads and bridges or homes and businesses, also can impact streamside habitats by compacting the soil, ripping up vegetation, and accidentally carrying in seeds of non-native or noxious plants.

Most people like to believe that our recreational activities don't harm habitats. But they can, sometimes, especially in wetlands. People enjoying nature may accidently trample or disturb vegetation. Hunters and others who use all-terrain vehicles may compact soil, dislodge sediment, and disturb amphibians and birds. Even campers can add to the problem when camping in meadows or beside streams and lakes.

Sites built for recreation may pose special problems. For example, golf courses can use huge amounts of water to keep their fairways and greens thick and lush. Water can come from underground sources. As these sources are extracted, they may lower the water table and dry out wetlands. Ski areas can impact wetlands in the surrounding forests and valleys when their developers build cabins and lodges, grade roads, and cut trails and ski runs.

What Happens When Wetlands Disappear?

Whether we are talking about flooded basements in the spring, entire downtowns swamped, or millions of pounds of soil washed downstream, destroying farmland, fisheries, and food for wildlife, the entire United States is at risk from increased flooding due to our destruction of wetlands.

Small-scale wetlands destruction can also have far-reaching effects. As they disappear, so too do their abilities to recharge groundwater, collect sediment, and trap pollutants. In addition, isolated wetlands often serve as crucial habitat for small populations of rare birds, insects, and amphibians.

The impact of wetland destruction occurs far beyond what we can see. Aquatic invertebrates are primary consumers in many aquatic ecosystems. They consume algae and other organic matter and later become food for other types of invertebrates and vertebrates throughout the food web. Some species are found only in a few springs or streams. Their loss could ripple out far beyond the isolated wetlands.

The loss of small, seemingly minor wetlands causes problems no matter where they are. For example, in urban areas, many construction crews ignore or are unaware of seasonal stream channels and ponds. They fill the depression in the ground without considering the impact of this change. But the resulting home or business owners will have to deal with the flash floods, wet basements, and swamped parking lots. Downstream water quality begins to suffer too and affects life from the smallest to the largest animals.

So what are we to do? Will our children be able to spend quiet fall mornings hidden among the tall grasses of wetlands, watching the autumn migration of ducks and other waterfowl? Laws have been written to protect the wetlands and should impact all aspects of wetland survival. Awareness can make a huge difference too. People who live and work near wetlands have a duty to help protect them from destruction.

Fun Links

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has a Wetlands Coloring Book — a fun look at wetlands just for you! While coloring these pictures or just looking at them you can learn about wetlands and the animals and plants that live in wetlands.

National Geographic Kids has a fun site where you can learn all about freshwater wetland habitats.

Check out Between Land & Water: The Wetlands of Idaho — from Idaho Fish and Game.

Environmental Protection Agency — The EPA has a lot to offer on wetlands. Its site includes information about different types of wetlands and great photos of existing wetlands with detailed descriptions.

Explore the National Wetlands Inventory from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — find maps and other important details about wetlands from all over the United States.

Get an international perspective on wetlands at Wetlands.org.

This interactive wetlands mapper from the US Fish & Wildlife Service shows the location of wetland habitats throughout the United States.

The Peril River is in trouble! Be an eco-detective and use your scientific reasoning and analytical skills to figure out who is damaging the river, and how to fix it!